Medical Changes Needed for Large-Scale Combat Operations

Successful treatment of combat casualties, for the most part, has become an expectation throughout the past eighteen years of combat operations. The U.S. military has the highest level of survival for preventable death in history, with a 92 percent survivability of battlefield injuries.1 The lessons learned in the treatment of these casualties have not been lost; however, when looking through the lens of large-scale combat operations (LSCO), many of these underlying assumptions and expectations cannot be taken for granted by commanders, soldiers, and the American public.

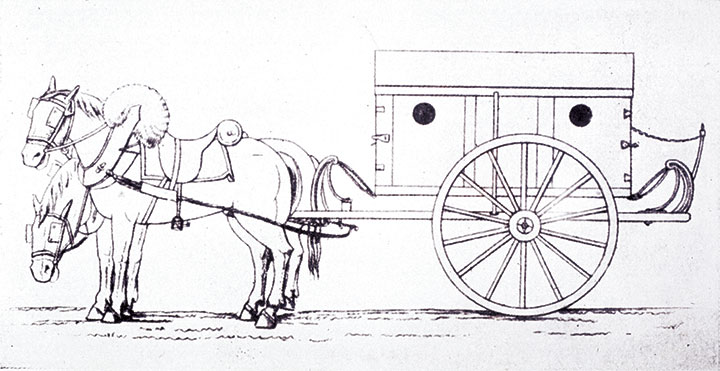

Changes in the nature of warfare required Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey to revolutionize medical planning and operations under Napoléon Bonaparte.2 Similarly, the transition to LSCO brings with it a multitude of challenges, not only for operational forces (e.g., fires integration, multi-domain threats, lack of air superiority) but also for all enabling functions including sustainment, protection, and intelligence. Medical considerations in LSCO have the same challenges. Reliance on past successes in wars in which we controlled the majority of operational variables does not guarantee success or readiness for the next war. A generation of officers and enlisted soldiers is unfamiliar with the medical actualities of prolonged, multi-corps fights against a peer or near-peer threat. Analysis and observations gained during Warfighter exercises (WFXs) identify areas in which the U.S. Army is not prepared for the medical realities of LSCO.

The Mission Command Training Program (MCTP) trains and evaluates division and corps operations in a simulated operational environment to test mission command, staff synchronization, and staff integration (vertically and horizontally) through WFXs. The WFX program uses an intricate and robust system of computer programs and technicians to simulate (not replicate) combat situations to force commanders and staffs to maximize their processes and utilize subordinate units to achieve operational goals. In contrast to recent operations, in LSCO, brigades and divisions are no longer the pinnacle of operational forces; rather, they are tactical units used by the corps in a singular or multi-corps fight to defeat a peer or near-peer adversary. In contrast to the counterinsurgency paradigm of the past eighteen years where the focus was on small-unit engagements with an enemy of limited weaponry, peer/near-peer threats possess a scale and lethality not witnessed since World War II.

Within the MCTP construct, divisions and corps fight for eight days. Based on last year’s five exercises, the average number of combat casualties (for a fighting force of approximately one hundred thousand) is consistently fifty thousand to fifty-five thousand: about thirty thousand to thirty-five thousand soldiers sustained wounds requiring evacuation out of theater, ten thousand to fifteen thousand were killed, and ten thousand to fifteen thousand were injured but able to return to duty. This is roughly the same number of casualties collectively incurred in Iraq and Afghanistan; however, the survivability percentage in Iraq and Afghanistan is significantly higher. Nevertheless, while injuries and death will occur in any war, it is the U.S. military’s collective responsibility to minimize the number of deaths and combat injuries.

Since combat operations must continue despite a large number of casualties, the United States must continue to provide personnel to fight the fight. All too often, the Army calculation of combat power is focused primarily on major end items like tanks, vehicles, artillery, and helicopters. Unfortunately, if there are a thousand tanks but only one hundred crews, there are effectively one hundred tanks and nine hundred road blocks. In order to maximize combat strength, the U.S. military must invest in the necessary medical infrastructure to care for the anticipated massive number of casualties (as well as in a robust personnel replacement system).

From the medical perspective, the primary focus of the Army Medical Department’s (AMEDD) previous motto “to conserve fighting strength,” has never been truer than now.3 This kind of focus incorporates everything from preventive medicine and day-to-day readiness to treating infectious diseases and performing lifesaving damage-control surgery. Historically, the impacts of noncombat medical issues greatly outnumber combat injuries; in my personal experience of eleven deployments in multiple operational assignments, over 90 percent of medical duties were for noncombat-related issues. The significance of nonbattle injuries is vitally important and cannot be overlooked because it dramatically affects combat power. Force health protection must be emphasized in all environments.

Lessons learned from the MCTP WFXs will highlight the medical realities of LSCO and will identify areas that must be addressed in order to minimize deaths and maximize the fighting force (combat power).

A Change in Thinking

As Gen. Mark Milley has repeatedly stated, the United States must be prepared for war on a large scale.4 The operational realities, the stresses upon the medical system and sustainment units, and the psychological and emotional impact of significant casualties cannot be underestimated and must be prioritized.

A large-scale war will resemble World War II in scale but will involve modern lethality. A day of combat could potentially incur three thousand to four thousand casualties daily, and the U.S. military’s medical system lacks the capacity (not the capability) to care for all of these casualties. Triage as we know it, namely that the most severely injured (who can survive) are treated first, will change. Not everyone who can survive will survive (there are not enough resources). Furthermore, the Golden Hour will become a goal, not an expectation. This is not a paradigm shift; instead, it would be a return to the patterns and expectations of World War II operations and Cold War planning, exacerbated by current technology and lethality. Lastly, although mass casualty situations will occur periodically across the battlefield, realistically, the entire operation will experience a continuous mass casualty environment.

The number of casualties will require massive investments into intratheater surgical and hospitalization capabilities. Furthermore, it will require a vast number of ground and air assets to medically evacuate the wounded to higher levels of care. As air superiority cannot be guaranteed, the threats to aviation assets could limit aerial medical evacuation (medevac), and thus, ground medevac will be the primary means of movement from point of injury to Role 2 treatment facilities (lab and holding capabilities, possibly surgical assets) and potentially to definitive Role 3 hospitals (full surgical services and ICU capability). However, tactical ground vehicles have limited litter transport capabilities. Therefore, when aligning the need for assets with the total number of casualties, the need vastly exceeds the medical system inventory in both direct patient care and in evacuation capacity. The resultant effect will dramatically increase died-of-wounds rates. Expedited transportation may be further limited by degraded road networks (due to enemy damage or threat), displaced civilians, and dense urban environments. Casualty evacuation by nonmedical platforms will be limited by an overall shortage of troop transport assets due to competing mission requirements.

To mitigate these challenges, medics, nurses, and providers at all levels must be trained and prepared for prolonged casualty care to maximize the survivability rates of wounded soldiers. The importance of Tactical Combat Casualty Care and lifesaving medical skills by all members of the military cannot be overstated.5 Individuals and leaders at all levels must prioritize medical skills training (combat lifesaver) and medical specialist training in order to preserve life and combat power. As demonstrated in Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom, when soldiers reach surgical treatment promptly, the AMEDD has the medical skills and capabilities to provide greater than a 90 percent survivability rate. However, AMEDD’s current structure and staffing lacks sufficient capacity for far-forward extended casualty care to meet these medical demands. The resultant effect will be a lower survivability rate and the inability to sustain the impressive gains and successes in tactical medical care witnessed over the past two decades. Lack of medical access and bed availability is even further compounded when considering the significant burden of noncombat casualty care demands from those with infectious diseases or other conditions requiring observation and hospitalization.

Assessing the medical realities of LSCO requires a significant shift in expectations from the counterinsurgency environment. As mentioned previously, no longer can surgical treatment within the Golden Hour be an expectation. Not only will air medevac be tactically unavailable at point of injury or from Role 1 (unit aid stations), but the assets necessary to move thousands of casualties to surgical facilities also do not exist. And even if the transportation assets were available, inadequate numbers of surgeons and operating tables translate to insufficient supply to meet the demand. Lastly, and potentially the most challenging change in expectations, relates to triage of casualties. The standard principles of triage may need to be reversed in order to maximize combat power. Instead of prioritizing casualties based on severity of injuries, determination of who gets treated first may be based on a utilitarian principle to maximize the number of service members who can remain in the fight (e.g., treating three to four individuals who can return to fighting versus one critically wounded individual who requires vast quantities of medical resources). Moreover, all of these considerations and challenges are magnified when in a chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear environment. All leaders, not just medical leaders, must wrestle with this reality and the resultant difficult decisions that must be made.

Direct and Indirect Effects on Combat Operations

The United States has one mission in war: to win! The majority of the focus in war planning and execution lies in maximizing lethality with weapon systems, employing the most successful tactics, and utilizing adjunct systems (such as intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; engineer support; and nonlethal assets). However, as proven throughout U.S. military operations, combat support planning and sustainment operations are critical for combat success. In the same manner that the sustainment community quickly resupplies units with ammunition, fuel, and repair parts, the human dimension must have similar attention during LSCO.